ChatGPT and Negotiating the Question

[This article was originally posted on Medium.]

ChatGPT is not going to solve your information retrieval problems…yet.

In the wake of ChatGPT’s mainstream media blitz, there has been significant chatter pitching ChatGPT as a revolutionary chatbot to help users find the information they need. The temptation to skip the complexity of true findability is not new. In recent history, the usual question is, “Can’t we just use machine learning?” In 2023, that question has become, “Will any of this matter once we get ChatGPT working?” There are two big reasons why ChatGPT isn’t going to solve our findability problems in its current form, and to illustrate why those reasons matter, I’m going to go back to my old friend Robert Taylor.

One of my favorite information-seeking behavior models is Robert Taylor’s “Levels of Information Need”, which I’ve written about previously. In that model, we see how a user goes through a series of back-and-forth information exchanges that move them through the process of “negotiating the question” when they’re seeking information to fill a need:

First you identify a visceral need, or “vague sort of dissatisfaction” that you might not be able to put into words.

Next, you formulate a conscious need that may be expressed as “an ambiguous and rambling statement.”

After you’re done rambling, you’re able to construct a formalized need, expressed as a “qualified and rational” statement.

Finally, you have a compromised need: a query you could actually put into a system and expect to get good results from.

In that article, I proposed that a well-designed chatbot would excel at helping a user move from a formalized need to a compromised need, or a query that will return relevant results, and then return results for that query. This proposal assumed two things, which I hypothesize are requirements for chatbot-assisted information retrieval:

The chatbot in question can retrieve objective information, and

The dialogue capabilities of the chatbot will help the user construct a formalized need.

These assumptions may be true for chat experiences optimized for information retrieval, but we’re now seeing chatbots that are optimized for different uses. ChatGPT on its own is very powerful, but it has shortcomings that lead me to say, “It won’t solve our retrieval problems just yet.”

(Note: Microsoft has announced a new AI-powered Bing search experience that supposedly meets both of these requirements, using a next-gen OpenAI model in combination with the Microsoft Prometheus model. An exciting development that I’ve yet to experience firsthand, but which illustrates my point: ChatGPT on its own isn’t optimized for information retrieval and has gaps that need to be addressed by combining it with other tools.)

ChatGPT, or Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer, is explicitly optimized for generating text in a semantically coherent way, not retrieving objective facts or timely information. This is not a secret, and the creators of ChatGPT have been very clear about the fact that it has certain limitations: “ChatGPT sometimes writes plausible-sounding but incorrect or nonsensical answers” because “during RL [reinforcement learning] training, there’s currently no source of truth.” Here’s an excerpt from a “conversation” where I ask ChatGPT to help me find a place in Seattle that will repair crystal wine glasses:

Me: does anyone in seattle do those repairs?

ChatGPT-3: I’m sorry, I don’t have a specific company to recommend in Seattle that repairs crystal wine glasses. However, you can try searching online for “crystal glass repair Seattle” or “glass restoration Seattle” to find local businesses that offer these services. You can also check with local glassware or home goods stores, as they may have recommendations for repair services. Additionally, you can ask for referrals from friends or family who have had similar repairs done in the past.

ChatGPT doesn’t fulfill our first requirement for information-retrieval because it is incapable of retrieving objective information. In fact, it specifically suggests I do an online search instead of asking it (at least it is humble in its shortcomings). ChatGPT is not a substitute for other information retrieval mechanisms, nor is it a substitute for content that is well-structured and has enough metadata to be retrievable by those mechanisms, including search and faceted navigation.

Structured information becomes more important in a world where new, usefully-accurate information needs to be generated, not less. Two recent studies have shown that training GPT models on both content and structured data about that content results in much better outcomes (here’s a study on modeling logistics systems and another on a knowledge-infused model for Entity and Relation Extraction). Structure and metadata are not only not being replaced by artificially intelligent features, they are actually becoming more relevant to the mainstream conversations about AI, as they can be important sources of truth when training models.

The more interesting requirement for an information retrieval experience mediated by a chatbot is “the chatbot must help the user construct a formalized need”. OpenAI highlights another known shortcoming of ChatGPT-3: “Ideally, the model would ask clarifying questions when the user provided an ambiguous query. Instead, our current models usually guess what the user intended.” It’s essential to note that this is a known shortcoming of ChatGPT, rather than an improvement on an old process.

Guessing what the user intended is no small feat. In “Levels of Information Need” Taylor writes: “Without doubt, the negotiation of reference questions is one of the most complex acts of human communication. In this act, one person tries to describe for another person not something he knows, but rather something he does not know.” The act of describing what you don’t know is HARD! One of the most fruitful ways we know how to do this is through dialogue, or iterative back-and-forth information exchange. Taylor writes more about this tactic during the second level of information need, the conscious need: “At the second level there is a conscious mental description of an ill-defined area of indecision. It will probably be an ambiguous and rambling statement. The inquirer may, at this stage, talk to someone else to sharpen his focus. He presumably hopes that two things will happen in this process: (a) his colleague will understand the ambiguities; and (b) these ambiguities will gradually disappear in the course of the dialogue.”

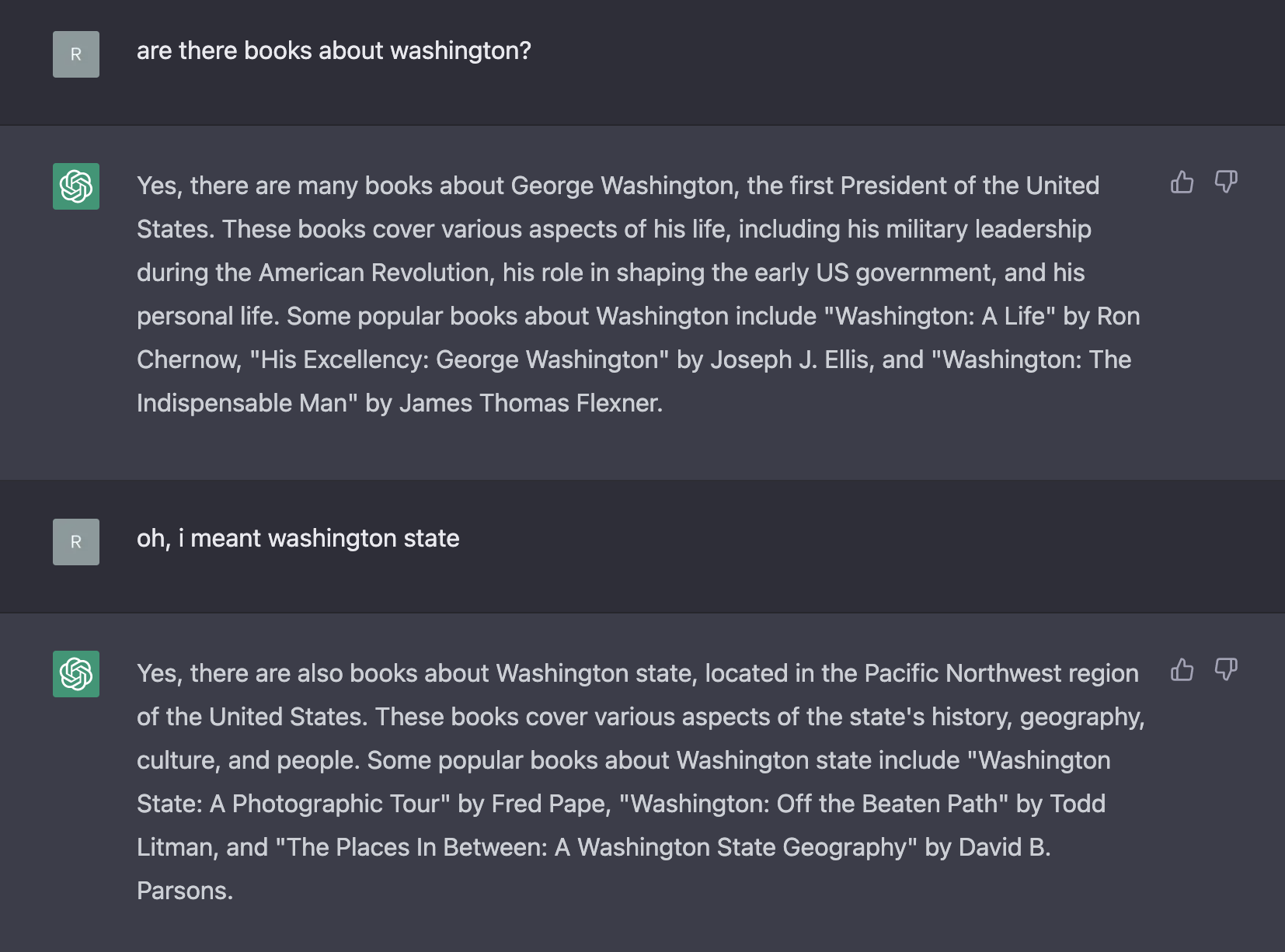

Because ChatGPT guesses intent rather than asking clarifying questions, it can’t be an active participant in dialogue and doesn’t take an active role in clarifying ambiguity. Let’s look at what happens when we try a few classic query negotiation prompts. First, we’ll ask for “books about Washington”:

Me: are there books about washington?

ChatGPT-3: Yes, there are many books about George Washington, the first President of the United States. These books cover various aspects of his life, including his military leadership during the American Revolution, his role in shaping the early US government, and his personal life. Some popular books about Washington include “Washington: A Life” by Ron Chernow, “His Excellency: George Washington” by Joseph J. Ellis, and “Washington: The Indispensable Man” by James Thomas Flexner.

Me: oh, i meant washington state

ChatGPT-3: Yes, there are also books about Washington state, located in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. These books cover various aspects of the state’s history, geography, culture, and people. Some popular books about Washington state include “Washington State: A Photographic Tour” by Fred Pape, “Washington: Off the Beaten Path” by Todd Litman, and “The Places In Between: A Washington State Geography” by David B. Parsons.

Ok, now let’s try asking if glasses can be fixed:

Me: can glasses be fixed?

ChatGPT-3: Yes, glasses can be fixed, depending on the issue. Common problems with glasses such as loose hinges, broken arms, and scratched lenses can often be repaired by an optometrist or an eyeglass repair specialist. If the frames or lenses are damaged beyond repair, they may need to be replaced.

Me: oh sorry, i meant crystal wine glasses

ChatGPT-3: Yes, crystal wine glasses can be fixed if they are broken or chipped. Some crystal glass repair companies specialize in repairing crystal wine glasses by filling in the chips and cracks with a clear resin that dries to a glass-like finish. This can restore the appearance and functionality of the glass. However, the repair may not be perfect and may affect the value of the glass, especially if it is antique or highly valuable. In some cases, it may be better to replace the broken glass with a new one.

Me: does anyone in seattle do those repairs?

ChatGPT-3: I’m sorry, I don’t have a specific company to recommend in Seattle that repairs crystal wine glasses. However, you can try searching online for “crystal glass repair Seattle” or “glass restoration Seattle” to find local businesses that offer these services. You can also check with local glassware or home goods stores, as they may have recommendations for repair services. Additionally, you can ask for referrals from friends or family who have had similar repairs done in the past.

In both examples, ChatGPT assumes an intent from an ambiguous query, rather than replying with disambiguating questions, as a human would. In both cases, the answer is so clearly inaccurate that I can provide an additional prompt to clarify “which Washington” and “which glasses”. In a human-to-human version of this interaction, my colleague would likely ask disambiguating questions before attempting to answer, because we all know what assuming does. “Do you mean Washington the person, or Washington the state, or Washington, D.C., the district?”

It’s obvious when ChatGPT guesses the wrong “Washington” or “glasses”, and seeing the obviously wrong response prompts me to correct the guess. But what happens when ChatGPT gives me an inaccurate response based on a guess that isn’t obvious? Without letting me know that it just made a whole bunch of assumptions, how can I discern the inaccurate response and provide the necessary correction? This is where relying on ChatGPT or similar experiences as our primary means of providing information to users starts to get dangerous. Without that disambiguation prompt, we’re skipping past our responsibility to help people spot inaccurate or potentially harmful content in the context of their information seeking process.

Beyond that, notice how much of the burden of asking the right question is on the user (so much burden, in fact, that prompt engineering has become mainstream with even Forbes writing “hacks and tips” on the subject). ChatGPT and other chat UIs supplement a part of the information seeking process but cannot support the entire process. In the case of ChatGPT, it can sort of help the user get to a real search query by being a passive sounding board while the user throws prompts at it, but it certainly doesn’t provide active dialogue or thoughtful assistance with the process. Think of it like hitting a tennis ball against a wall to practice your tennis game — you’ll get some repetitive practice and work up a sweat, but the wall is not going to coach you on your technique. With ChatGPT, we’re not taking any of the burden of query negotiation off of the user, we’ve just put it into a novel interface: narrative chat. Once the novelty of prompt engineering wears off, it will revert to being just plain annoying having to do all that prompting work just to get information.

ChatGPT is extremely exciting. Its capabilities change daily, and I am eagerly looking to use it for expanding and summarizing text, which it does beautifully. I also hope that someday I will have to update this article to say that it negotiates queries spectacularly. Right now, though, it is not a panacea for information retrieval challenges because it cannot retrieve objective information very well and it does not add new value to the query negotiation process — it does not actively help the user move from a conscious need to a formalized need in the way that it feels like it should. For now, let’s use ChatGPT for what it’s great at: telling incredibly mediocre information architecture jokes.

me: tell me a knock knock joke about information architecture

ChatGPT-3: Knock, knock!

Who’s there?

Boo.

Boo who?

Don’t cry, it’s just a usability test!

Many thanks to Sarah Barrett for her unparalleled citation chaining habits and for having memorized classic query negotiation prompts to test with ChatGPT-3.